Blog > Understanding The Real Housing Inequities in Minnesota

Understanding The Real Housing Inequities in Minnesota

Minnesota's housing history is deeply intertwined with systemic inequities that have shaped its communities and perpetuated disparities, particularly along racial lines. To fully grasp the current landscape, it's essential to delve into the historical practices that laid the groundwork for today's challenges.

The Genesis of Racial Covenants

In the early 20th century, as Minneapolis expanded, developers and real estate professionals sought methods to control and influence the racial composition of neighborhoods. This led to the introduction of racial covenants—legal clauses embedded in property deeds that explicitly prohibited individuals of certain races, particularly African Americans, from purchasing or occupying land. The first recorded racial covenant in Minneapolis dates back to 1910, initiated by developer Edmund Walton. These covenants were not isolated incidents but became a widespread tool, systematically used to enforce segregation. By restricting property ownership and residency based on race, these covenants effectively confined African American families to specific, often less desirable, areas of the city.

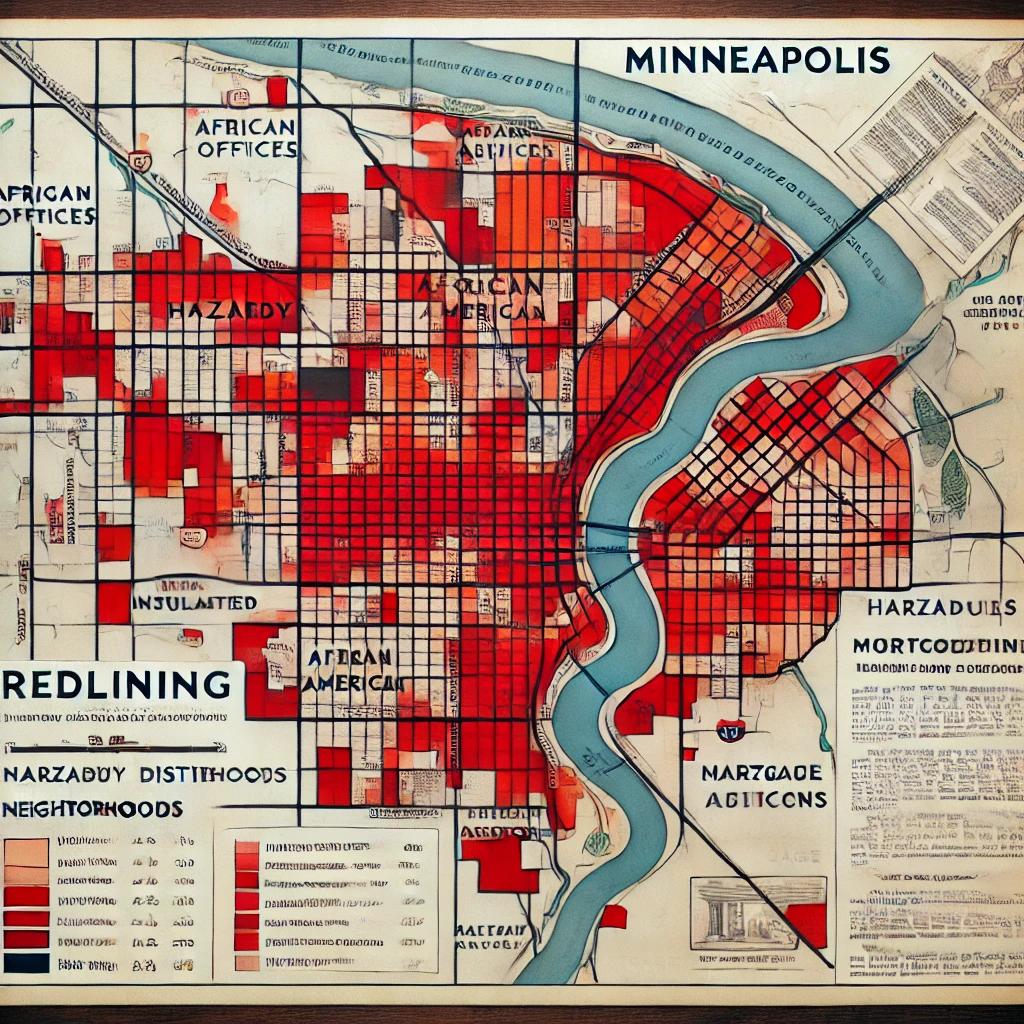

Redlining: Institutionalizing Discrimination

The 1930s introduced another layer of systemic discrimination through the practice of redlining. The Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal agency, created "residential security maps" to guide investment decisions. Neighborhoods were color-coded based on perceived investment risk, with areas inhabited predominantly by African Americans marked in red, signifying them as "hazardous." This designation led to widespread denial of mortgages, insurance, and other financial services to residents in these areas, stifling economic growth and homeownership opportunities for communities of color. The ramifications were profound, as redlining not only limited individual financial mobility but also devalued properties in these neighborhoods, creating a cycle of disinvestment and decay.

The Arthur and Edith Lee House: A Case Study in Resistance

A poignant example of the personal toll of these discriminatory practices is the story of Arthur and Edith Lee. In 1931, the Lees, an African American couple, purchased a home in a predominantly white neighborhood in South Minneapolis. Their presence was met with hostility; large crowds gathered to intimidate and force them out. Despite facing violent threats and social ostracism, the Lees, with support from local civil rights advocates like attorney Lena O. Smith, stood their ground. Their resilience highlighted the pervasive nature of housing discrimination and the courage required to confront it. Today, the Arthur and Edith Lee House stands as a testament to their struggle and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Urban Renewal and Highway Construction: Displacement Under the Guise of Progress

Post-World War II urban renewal projects and highway constructions further disrupted African American communities. In Minneapolis, the construction of Interstate 35W in the late 1950s and 1960s led to the displacement of entire neighborhoods, particularly those predominantly inhabited by African Americans. These projects, often justified as necessary for urban development, disproportionately targeted minority communities, leading to loss of homes, businesses, and community cohesion. The physical scars of these developments are still visible today, serving as reminders of the communities that once thrived there.

Legislative Responses and Their Limitations

Recognizing the injustices, Minnesota took legislative steps to address housing discrimination. In 1953, the state banned new racial covenants, and in 1962, it prohibited housing discrimination based on race, religion, and national origin. These measures were precursors to the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968. However, while these laws marked progress, they couldn't immediately undo the deeply entrenched patterns of segregation and inequality. The legacy of decades-long discriminatory practices couldn't be erased overnight, and their effects lingered, influencing socioeconomic dynamics for years to come.

The Lingering Impact

The historical practices of racial covenants, redlining, and discriminatory urban development have left an indelible mark on Minnesota's housing landscape. Today, areas that were once subject to these practices often correlate with neighborhoods facing economic challenges, underfunded schools, and limited access to essential services. Moreover, the racial homeownership gap in Minnesota remains one of the largest in the nation, a stark indicator of the enduring impact of past injustices. Understanding this history is crucial for informing current policy decisions and fostering a more equitable future.

What's Next?

Minnesota's journey through housing inequities is a complex tapestry woven with policies and practices that systematically marginalized communities of color. By examining this history in detail, we not only honor the experiences of those who endured these injustices but also equip ourselves with the knowledge needed to challenge and change the structures that perpetuate inequality. As we move forward, acknowledging and addressing this legacy is essential in building a more inclusive and equitable society.

I, Ken Alger, as Vice Chair of the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee for Saint Paul Area Assosciation of Realtors am dedicated to ensuring equitable and fair housing for all. EXIT Realty Springside is an supporter of equal and fair housing for all.